“A New Architecture for a New City”

by Alan Hess

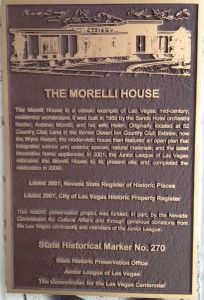

In Las Vegas the past is often overlooked, forgotten or demolished in the rush to the future. The historic Antonio and Helen Morelli house preserved by the Junior League of Las Vegas, however, is a vibrant reminder of the newness, optimism, and style in Las Vegas in the mid-twentieth century. The house’s bold horizontal lines, glass walls, open plan, and natural materials embody the fundamental tenets of Modern architecture and Modern living in that period.

When Antonio R. Morelli arrived in July 1954 to assume the role of musical director for the Sands Hotel, he was one of thousands of people who came from someplace else to take advantage of the new possibilities in Las Vegas. The Sands was the most recent and most stylish of the seven luxury motor inns strung along the county highway, colloquially known as The Strip. These hotel-casinos and the Desert Inn Estates neighborhood where the Morellis built their home in 1959 were emblematic of the new suburban metropolises that evolved in Las Vegas and other southwestern cities during the twentieth century.

These cities used Modern architecture, a style that satisfied the public imagination for all things new. Today it has been given the label “Midcentury Modern” to identify the unique boom of creativity and construction in the three decades after World War II.

Antonio Morelli’s Journey to Las Vegas

Las Vegas represented a blank slate for anyone seeking to begin anew in a fresh, accommodating environment, whether one was a divorced mother looking for a decent wage as a waitress or croupier, a big city gambler looking for a place to ply one’s trade without the stigma of illegality, or a fifty-year-old musician/promoter adapting to major changes in the entertainment industry.

Born July 22, 1904, in Rochester, New York, Anthony (“Tony”) Morelli grew up in Erie, Pennsylvania, as one of nine siblings. His father took him to Italy in 1914 to be educated, first briefly at Milan’s San Celso Military Academy and then (more suited to his interests) the Royal Conservatories of Music in Milan and Parma. Returning to the United States in 1925, Morelli traveled the country as a pianist, promoted vaudeville acts, wrote music and arrangements for theater productions (including several Radio City Music Hall productions), and conducted theater and civic orchestras around the country throughout the 1930s and 1940s. When he married Helen Collins in 1935, he was the orchestra leader for the newly opened RKO Palace Theater in Albany, New York. She was secretary to Harry Rogers, a New York producer and advertising agent.

Morelli first visited Las Vegas in 1953 with the Olsen and Johnson comedy team. When he accepted Sands president and impresario Jack Entratter’s offer to become the new hotel’s musical director the following year (he had known Entratter from the Copacabana Club in New York), Morelli stepped into a newly minted realm of entertainment. The brash young town in the middle of the desert had a glittery, nouveau riche reputation, and the casinos and hotels were known to be run by various crime syndicates. Entratter believed that Morelli’s reputation as a classically-trained musician brought a polish that would attract wealthy, educated people. In his twenties Morelli had adopted a courtly mustache, waxed into penciltip endpoints, as his trademark – a symbol of his classical training even as he worked in the very heart of mid-century popular music in Las Vegas, where he was officially known as Antonio.

Morelli made the switch to Las Vegas at the right time. The theater circuit that had supported him before World War II was dead. Television was bringing entertainers into everyone’s home, and for free. Yet in Las Vegas enormous gambling revenues could underwrite astronomical fees that attracted the biggest stars in show business to perform live.

Though not a major figure in Las Vegas show business, Morelli characterized the professional mid- management personnel who helped turn Las Vegas into a smoothly functioning, highly professional, widely popular entertainment venue. His boss Jack Entratter brought in the stars who attracted the high-rolling gamblers coveted by the hotels. The big stars would usually bring their own musical directors for their acts, but Morelli wrote arrangements and rehearsed and fronted the eighteen-member regular orchestra, reportedly the largest on the Strip. The billing on the great Sands sign on the Strip read “Antonio Morelli and his Orchestra.” He worked with Sammy Davis, Jr., Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Danny Thomas, Jerry Lewis, Florence Henderson, Red Skelton, Dean Martin, and others. He also played a role in one of the most memorable scenes in twentieth century American popular culture: the Rat Pack appearances of Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Joey Bishop, and Peter Lawford at the Sands in 1960. In films of the performances, Morelli can be glimpsed as the tall, smiling, elegantly mustachioed bandleader behind the Rat Pack’s antics.

Today only traces of Morelli’s work as a musician remain in recordings. But in his lifetime he saw himself in the role of a solid citizen bringing high culture to the rough Western city. He produced and conducted the free Las Vegas Pops concerts (called “Shirt Sleeve Symphonies”) virtually from his arrival in the city. He also composed and conducted special Easter Morning and Christmas services for the public. He later set up a scholarship for young musicians at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. Through a series of happy accidents, we have today the house he built for his wife and himself, the very embodiment of Las Vegas’s optimism about the future in its mid-century boom years.

Desert Inn Estates

Almost four years after Morelli began work at the Sands, he felt secure enough to set down roots and build a home in 1958. Helen had delayed her permanent move from their Long Island home until 1957. It was a sizable investment–other homes in Desert Inn Estates sold for $32,000 at a time when the average new mass-produced house sold for less than half that amount. But the neighborhood and the house’s modern style both conveyed a prestige worthy of the expense. They selected a lot at 52 Country Club Lane (originally Twain Road) in the Desert Inn Estates, already one of the poshest neighborhoods in town. The Desert Inn Hotel developed the property in 1952 as a series of sixty-five quarter-acre custom homes sites around the golf course behind the Desert Inn hotel bordered by the present day Desert Inn, Paradise, and Sands boulevards. The Modern style was set by the original club house at the Desert Inn Country Club, designed by Powers, Daly and DeRosa. A thoroughly modern design, it had large glass windows set in a framework of steel beams.

Desert Inn Estates embodied the ideal of suburban living. Single family homes, most with swimming pools, sat in a beautifully landscaped setting but within an easy automobile drive to shopping and work. Morelli had a one-mile commute in his Cadillac convertible to the Sands. Antonio and Helen shared this neighborhood with many members of Las Vegas’ natural aristocracy in the entertainment industry, including singer Keely Smith, actress Betty Grable and band leader Harry James, and Desert Inn founder Wilbur Clark. Doctors, realtors, power company executives, and the family of future governor Bob Miller also lived there; Howard Hughes’ right hand man Robert Mayheu had a home in Desert Inn Estates; and Hughes press secretary Kay Glenn bought the Morellis’ house in 1978.

Building Las Vegas ’ Modern Residential Neighborhoods

A city’s homes reflect the fashions, technology, and society of the times in which they are built. The ornate nineteenth century brownstone townhouses on the crowded streets of Boston, New York and Baltimore, for example, represented solid, up-to-date, middle class housing for their times. In the 1950s and 1960s much of the new wealth growing with Las Vegas’ expansion demanded Modern architecture, the style associated with progress and prosperity. The same trend could be seen in all the newly developing cities of the Sunbelt, from Florida to California.

Development of Modern Architecture

Southern California pioneered a simple, original modern architecture oriented to the out-of-doors since the 1910s in the work of Irving Gill, R. M. Schindler, Richard Neutra, Lloyd Wright, and Frank Lloyd Wright. In the 1920s and 30s, many considered this architecture wildly avant garde – acceptable to an extent in a new city like Los Angeles but not generally favored by the tastemakers in more traditional cities. By the 1950s, however, this style enjoyed a wider acceptance especially by the middle class. In the boom years for construction after World War II, a host of talented young architects explored the possibilities of new materials for the new lifestyles and benign climate of the West.

These architects developed several varying approaches. Architects such as Pierre Koenig, Raphael Soriano, William Cody, Richard Neutra, Albert Frey, Craig Ellwood, and Allyn E. Morris often used steel, lending their designs a crisp regularity. Others such as Whitney Smith, Wayne Williams, and A. Quincy Jones often used wood construction. Many of these architects participated in the Case Study program (1946-1966), a series of houses sponsored by Arts + Architecture magazine that became one of the most famous promotions of Modern design in the era. Like the simple geometries of the European-based Bauhaus Modernism of the 1920s, abstract flat-roofed boxes and exposed skeleton frames often dominated their aesthetic appearance. With the structure carried on a light frame instead of loadbearing walls, living room, dining room, kitchen and family room spaces often flowed together in one open plan. Phoenix boasted similar work by Alfred Beadle, Ralph Haver, and others, demonstrating the common interest in Modernism shared by many western cities. The work of these architects was widely published in the leading architecture magazines and spread throughout the world as a distinctive interpretation of Modern ideals.

The Morelli house’s more moderate version of Modern design relates to the work of Southern California architects Allen Siple, Edward Fickett, Paul R. Williams, the early work of E. Stewart Williams and, in Tucson, Arthur Brown. In these houses the geometries are less rigorous or crystalline than in the squared-off Case Study houses. Instead of emphasizing the structural framework, they compose walls, planar roofs, and glass planes into a more relaxed collection of forms articulated in wood, stone, or stucco.

Mr. Morelli Builds His Dream House

For his own house, Morelli proved to be an active client. He and his wife Helen knew what they wanted in terms of rooms and features and hired architect Hugh E. Taylor (who designed several other houses at the Desert Inn Estates) in 1958 to develop these ideas. Like many other Southern California architects, Taylor found Las Vegas an appealing place to practice architecture in the 1950s. After studying at the University of Southern California, he first worked in Los Angeles and then, after arriving in Las Vegas in 1948, on the much-delayed Desert Inn Hotel with client Wilbur Clark. The clean horizontal lines of the Desert Inn’s large sheltering roof (the designated originated with architect Wayne McAllister) complemented expanses of natural desert stone walls and floors. Taylor settled into a long career in Las Vegas, designing the original Sunrise Hospital, Country Club Towers, and many custom houses in other upscale subdivisions such as Rancho Circle.

At 2800 square feet as originally built, the house was comfortable for a couple without children but allowed for guests, plus the Morellis’s French poodle named Mozart. Entertaining was an important function because of Morelli’s work with stars performing at the Sands. The final design used the open plan that Modern architecture encouraged to create a large living room-dining room with tall ceilings and sliding glass doors that opened to the patio overlooking the golf course. The kitchen and family room off one side of the living room are equally spacious, combining cooking areas, an informal dining area with banquette, and TV cabinet. On the opposite side of the living room, a short hall leads to the master bedroom suite and a guestroom.

On its original site, the house sat sixty feet back from the road, with a walled yard and an irregularly angled swimming pool in the front. The tall, pavilion-like entry looked out onto this pool terrace, as did the guest room’s sliding glass door. In place of traditional applied ornament, this modern design exploits its materials to add texture and detail. Screens of ornamental concrete block against the stucco walls similar to those used by Edward Durell Stone at his celebrated 1958 American Embassy in New Delhi caught the brilliant sun and deep shadows and bestow a lightness on the wood frame structure. These richly filigreed surfaces contrasted with the plain stucco walls decorated with wide vertical wood battens on the bedroom and kitchen wings. Morelli’s studio, built of concrete block, stood to the right of the front door, with an open carport for the couple’s Cadillacs between the studio and the street.

THE MORELLI HOUSE

The house’s structure is a modified wood post-and-beam system. While most of the Desert Inn Estates houses were built on a poured concrete slab, the Morelli house has wood joist floors on a perimeter foundation of concrete block, creating a small crawl space for access to the plumbing. Inside, the wood frame is exposed in the living room to highlight the natural beauty of the wood grain and the geometric simplicity of the structure’s efficient column spacings seen in the large window wall and sliding doors that originally overlooked the golf course.

The Morelli house uses a loose, asymmetric set of forms that relate to a less severe interpretation of Modern architecture than the rectangular Case Study houses. In this view of Modern design, the walls, ceilings, dropped ceiling soffits and fireplaces are treated as an abstract composition of interlocking planes that subtly define the entry, living, and dining spaces – a common goal of Modern design. The living room’s high ceiling also allows a line of clerestory windows along the front that balances the light from the large window wall. The roofs on the bedroom wing to the left of the entry and the kitchen wing to the right are lower and taper to a prow-like point at each end.

Two-by-six tongue and groove wood plank ceilings continue throughout the house. In the living room a low soffit along the front modulates the taller and lower spaces of the room. The high wood plank ceiling, resting on exposed horizontal beams, stretch past the glass wall to create a wide eave over the patio. Modernistic lights hang from every other beam providing downlight for the patio and uplight reflecting off the ceiling. This feature blurred the line between indoors and outdoors – another common goal of Modern design. The obscured glass surrounding the front door is an unusual, roughly corrugated pattern that adds an irregular texture. Artist Isabel Piczak designed the panel of stained glass in an abstract pattern high above the door. The Morellis also commissioned her to design one of the stained glass windows in the 1963 Shrine of the Guardian Angel church (designed by architect Paul R. Williams east of the Strip), a sign of the Morellis’s community involvement as well as the respectibility of Modernism in the growing city.

Another common theme in Modern architecture, the beauty and simplicity of natural materials, is repeated in the wood ceilings that are left unpainted to reveal the natural grain and the wood paneling of the living room. Another Modern detail is the roughly textured white marble stone wall setting off the pleated copper fireplace hood over a floating hearth. Instead of a formal mantle featuring carved wreaths, the simple yet bold geometry of the wedge-shaped fireplace hood becomes the dominant focus of the living room. Adding another note of modernity, the drapes on the large windows could be pulled aside at the push of an electric button.

Though the house is Modern, Morelli’s Italian heritage is seen in certain decorative elements. The low cabinet-partition at the entry for storage and displaying china are faced with decorative, semi-baroque screens and trim that soften the severity seen in some Modernist design. Unlike the boldly Modern Vladimir Kagan furnishings now displayed in the house, the Morellis’ furnishings were moderately and comfortably traditional, while complementing the open spacious of the architecture. Classical busts and other antique furnishings decorated the space, and luxuriously swagged curtains covered the front windows.

The master bedroom is carefully designed with high ceilings modulated by dropped soffits. Corner windows looked out over the golf course. Separate dressing areas for Helen and Antonio with built-in closets and wardrobes lead to the master bathroom which features dual sinks, an open step-down shower, and custom plumbing fixtures. Tiled with a custom turquoise gold-flecked ceramic tile, the open shower and dual sinks have some of the character of a luxurious steam room.

The kitchen-family room originally included an alcove for Morelli’s music studio next to a small kitchen. By the early 1960s the Morellis built an addition between the kitchen and carport for a separate studio, with its own exterior entry, in order to isolate sound. They also enlarged the kitchen to its present size.

The kitchen boasts an antique-copper colored oven, refrigerator and stove cook-top hood, now classics of mid-century product design. The large built-in island in the kitchen is faced with a large pleated upholstery, echoing the appearance of a stylish Las Vegas restaurant lounge of the period. Large, egg- shaped, frosted lighting globes hang from the wood plank ceiling. Conical downlights are also used; small holes puncturing their sides add a sparkle as the light shines through. The breakfast area has a custom designed television cabinet that swings out from the wall to create a fully-equipped bar for entertaining.

At the far end of the kitchen, a partition with built-in cabinets allows light from the clerestory windows beyond to reach the kitchen and family room area. In the kitchen, family room, and utility room areas of the house, original linoleum flooring uses white streaks against an orange matrix set in a grid of blue-green stripes. The Morellis had converted the half-bathroom into a laundry room, but the Junior League converted it back into a bath when it restored the house in 2007. The use of such colorful, modern manufactured materials and design patterns is another level of design making the house an expression of its mid-century, modern era.

Modern design frequently responded to local climate and site conditions, and the Morelli house exhibits many intentional adaptations to the Las Vegas desert. Its extreme heat prompted Taylor to add wide overhangs to shade the glass window walls and clerestory windows. The flat roof is a built up roofing covered in large crushed white rock to reflect the heat and add a natural desert texture. For year round living, Morelli also included a mechanical air conditioning system. As he had worked with Taylor, Morelli also worked actively in the actual construction of the house with his builder, Richard Small, the head carpenter at the Sands Hotel. Working with Small and Taylor, Morelli added many customized details as they went along. For example, the unusually tall sink in the master bathroom was added as an afterthought when the tall Morelli decided he wanted a sink comfortable to his height.

Conclusion

The Morelli House is a mature and excellent design that illustrates the popularity and progressiveness of Modern architecture in mid-century Las Vegas. While its design did not introduce innovations like those seen in cities such as Los Angeles, it does demonstrate Las Vegas’s status as a Modern city. Las Vegas’s Modern designers excelled particularly in the innovative public and entertainment architecture of the Strip. Along with those buildings, the Morelli House and other remaining Modern homes create a strongly unified built landscape that constitute one of the greatest modernist cities of the era. Thanks to the Junior League of Las Vegas’s conservation of the Morelli House, this significant aspect of Las Vegas culture, character and history has been preserved as an important historical resource for many years to come.

Home | Back to top | Historic Significance | Validation of Significance